Kishore Mahbubani explores the prospects of a joint Chinese-Indian defence of globalisation.

The biggest contradiction in global governance can be described succinctly. We live in times of massive change, with enormous shifts of power. Yet, our Global Governance Institutions (GGIs) remain virtually frozen, resistant to change. It doesn’t take a political genius to predict that political explosions will come in the arena of global governance.

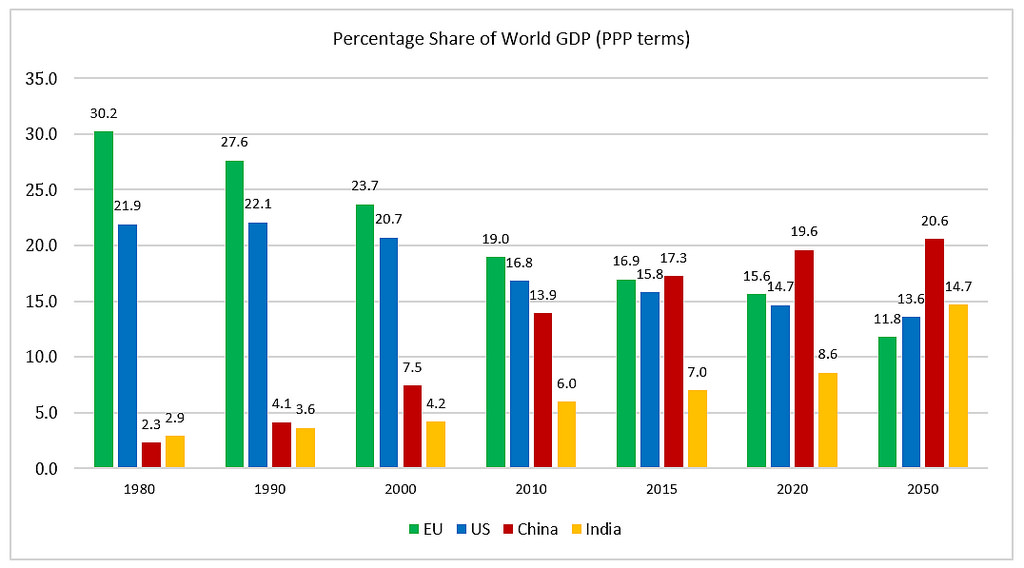

A short historical perspective is needed to understand the scale and speed of change. From the year 1 to 1820, the two largest economies were always those of China and India. It’s only 200 years ago that Europe exploded in economic power, followed by America. Hence the past 200 years have been a major historical aberration. China and India will inevitably return to their number one and two positions. PWC predicts that this will happen by 2050. China has already surpassed America as the world’s largest economy in PPP terms in 2014.

Unfortunately, most of our GGIs were created in the 1950s at around the lowest point of China’s and India’s economic fortunes. From a combined share of about 50% of the world’s economy in 1820, they had shrunk to less than 5% by 1950 . All this is reversing powerfully, as demonstrated in Figure 1. However, none of the GGIs seem ready to deal with these new economic and political realities.

Data Sources: 1980-2020 – IMF Database (2016 Economic Outlook). Accessed 3/3/2017. 2050 – PwC GDP Projections.

Data Sources: 1980-2020 – IMF Database (2016 Economic Outlook). Accessed 3/3/2017. 2050 – PwC GDP Projections.

In theory, the two most powerful economic GGIs, the IMF and the World Bank (WB) should be the easiest to reform as the voting shares for decision-making are supposed to reflect countries’ share of the global economic pie. In practice, change is difficult. Even after the IMF Board agreed to allocate China a bigger share from 2.928% to 6.068% in 2008, the US Congress held up ratification for 8 years, even though the US had nothing to lose from this new formula. Such is the irrationality in the discourse on global governance issues. To make matters worse, even though the G20 meeting in April 2009 in London agreed that the leaders of IMF and World Bank should be chosen by merit not nationality, the subsequent appointments to these positions reflected the old patterns of allocating the positions to Europeans and Americans respectively. Even today, it is uncertain that a Chinese or Indian will ever be chosen to lead these two institutions.

To balance this, it should be noted that until recently, China and India were widely perceived to be naysayers in the global governance system. They were seen to be obstructionists, rather than constructive consensus builders, in the global negotiation processes. The discussion on climate change reflected this. The Copenhagen Summit in 2009 failed because China and India refused to budge from their (politically justifiable) position that since climate change had been initiated by the “stock” of greenhouse gas emissions produced by the Western industrial countries, these countries should bear the burden of picking up the economic costs of dealing with climate change.

It would have been perfectly natural for China and India to dig in their heels and refuse to budge on climate change. Somewhat astonishingly, both have made massive U-turns. These U-turns were rational. All the studies showed that both China and India would suffer enormous damage from climate change. President Xi Jinping wisely said in Geneva in January 2018, “Until today, Earth is still the only home to mankind, so to care for and cherish it is the only option for us mankind.” PM Modi has quoted a famous Sanskrit saying “This is mine, this is yours, only mean-minded people indulge in keeping count in this manner. For the generous-minded, the entire world is one family.”

The world should have been breathing a huge sigh of relief that China and India have begun to behave constructively on many global governance challenges, from climate change to global terrorism, from global financial crises to pandemics. Sadly, politics can interfere with what has been a global thrust towards common sense in handling global challenges.

On climate change, the positive U-turn by China and India has been nullified by the negative U-turn of America with the election of Donald Trump. It is actually quite shocking that even though the Paris Agreements imposed no specific obligations on its signatories, Donald Trump decided to loudly announce America’s withdrawal. His “America First” policy clearly implies a “World Last” policy. Any meaningful collaboration between America and the rest of the world will probably have to wait till the arrival of a new American President.

Unlike America, Europe has not changed course on climate change. Indeed, Merkel has responded to Donald Trump’s U turn by saying, “’We Europeans must take our destiny into our own hands.” A natural opportunity has therefore surfaced for Europe, China and India to provide leadership to manage global challenges. Sadly, here too politics has intervened. Both China and India are blessed that they have exceptionally strong leaders, Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi, at a crucial point in their historical return to greatness. Initially, all the signs were that Xi and Modi would cooperate and collaborate. More recently, there has been a political falling out, partly triggered by a small military standoff over the Sikkim border. As a result, Xi and Modi failed to have an official bilateral meeting on the sidelines of the G-20 meeting in Hamburg in July 2017.

This downturn in China-India relations could not have come at a worse time in meeting rising global challenges. Given the massive backlash against globalisation both in America and Europe, and as China and India naturally emerge as new winners of globalisation in their return voyage to their number one and two positions, this would be a perfectly natural moment for China and India to collaborate strongly and preach (in their own collective self-interest) the virtues of globalisation. As President Xi Jinping wisely said in Davos in January 2017, “We should adapt to and guide economic globalization, cushion its negative impact, and deliver its benefits to all countries and nations.”

If China were to launch a massive defence of globalisation on its own, the impact, especially in the West, would be limited. Western trust of China is limited but their trust of India is greater. Hence, a joint Chinese-Indian defence of globalisation would naturally work better. At the same time, rising divisions between China and India would also mean that any meaningful effort to reform GGIs would be stalled. The old order would carry on longer.

The choice facing China and India is therefore clear. If both are to fully enjoy the rich opportunities flowing their way, they are likely to get there sooner if they can overcome their bilateral differences and cooperate and collaborate on global governance challenges. At the end of the day, this is probably the biggest leadership challenge that Xi and Modi face: can they bring China and India together to collaborate on rising global governance challenges?