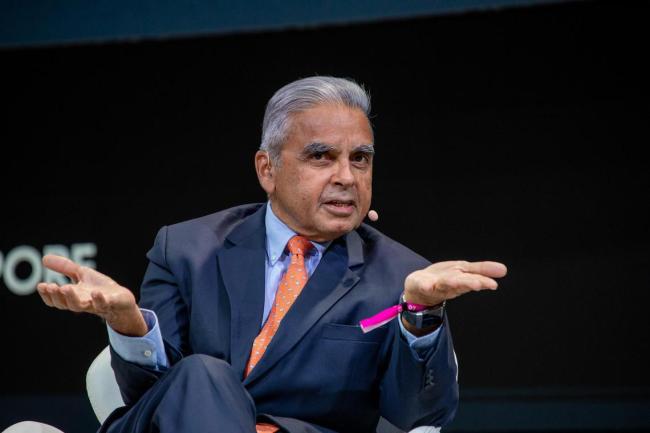

On a good Saturday morning, unencumbered by phone calls or text messages, Mr Kishore Mahbubani can churn out 3,000 words on paper – by hand.

But the 75-year-old former diplomat, who recently published his autobiography, Living The Asian Century: An Undiplomatic Memoir, makes one point clear – he must have his favourite music playing in the background while he writes.

“If I don’t listen to Mohammed Rafi, I cannot write,” he tells tabla during an interview at his office at the National University of Singapore, where he is an honorary Distinguished Fellow.

“Old songs from the 60s and 70s; I don’t listen to new ones. The songs I used to listen to growing up, I think they sort of wake up the childhood neurons of my brain.”

It’s one of many Indian traits Mr Mahbubani proudly possesses, amid an otherwise quintessentially Singaporean persona and outlook.

He is quick to remind me of this when I ask what it was like growing up in Singapore as a minority within a minority – Mr Mahbubani is of Hindu Sindhi descent.

“The paradox about my life is that, for some strange reason, many of my best friends are Singaporean Chinese,” he says.

“And I mentioned that in chapter one (of my memoirs), where my oldest friend, Jeffrey Seung, remembers me going to the coffee shop to bring my father home after he had been fighting with a broken beer bottle. So I’ve had very old Chinese friends. Of course, I do have Indian friends too.”

Mr Mahbubani’s autobiography chronicles his difficult, impoverished childhood and journey from a textile salesman in his late teens to serving as Singapore’s permanent representative to the United Nations between 1984 and 1989, and again between 1998 and 2004.

He later also served as president of the United Nations Security Council between 2001 and 2002. A large part of the book is devoted to his views on governance and international diplomacy.

The second of four children, Mr Mahbubani writes about how his father struggled with drinking and gambling habits, and was ultimately jailed for nine months for criminal breach of trust after he gambled away some of his employer’s money.

“Even though my sisters and I resented (and sometimes hated) our father when we were young, I came to forgive him when I understood that life had dealt him a very bad hand,” he writes.

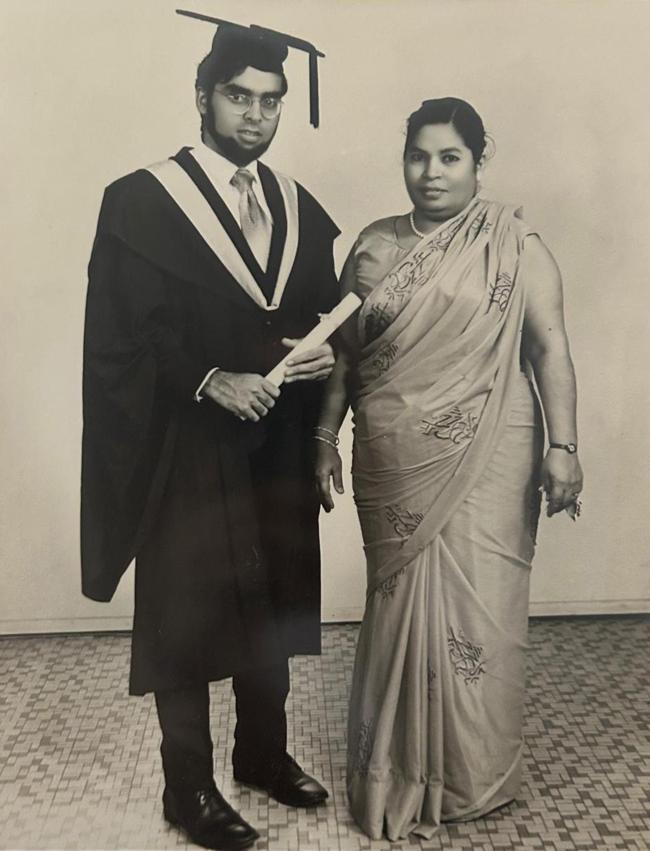

His mother Janki was the family’s stabilising force. Her mantra to the children was: Even though poor, they must not reveal this or complain about it.

“In her words, ‘even if you are feeling hungry, don’t show it. Put butter on your lips and smile’,” he writes. “For a large part of my life, I walked around with deep insecurities while smiling with metaphorical butter on my lips to give the impression that all was well.”

Working as a textile salesman for $150 a month, Mr Mahbubani’s life took a fateful turn when he was awarded the President’s Scholarship in 1967 to study at the then University of Singapore. The scholarship came with a government bond, and he joined the Foreign Ministry in 1971.

He rose quickly. Two years later, when he was 24, he became charge d’affaires of the Singapore embassy in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Postings to the Singapore missions in Kuala Lumpur and Washington soon followed.

In 1984, when he was just 35, Mr Mahbubani succeeded Professor Tommy Koh as Singapore’s permanent representative to the United Nations in New York.

Later, he became permanent secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and in 2004, entered the realm of academia when he became the founding dean of the National University of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

His books on geopolitics – he has penned 10 to date – and the articles he has written in international media have made him a sought-after commentator on Asia’s rise.

I pose a question to him on the influx of immigrants to Singapore and the government’s stance on the matter, which is controversial to say the least among some quarters. I cite a recent quote from Prime Minister Lawrence Wong who spoke about Singapore as an open society, where he also said there are “house rules” for immigrants living and working here.

But just what do these “house rules” entail?

“What he meant by that is that we are a multiracial society where we show a lot of respect for the other communities,” Mr Mahbubani says.

“Do you remember the famous play by Alfian Sa’at, Cook A Pot Of Curry? It’s about how a Chinese family that arrives in Singapore complains about the curry smell emanating from their Indian neighbours’ home.

“And then over time, the Chinese family adjusts to it. So I think that’s what it means – respect for other communities.”

He continues: “And that’s something that many who come to Singapore don’t understand and appreciate, right? In my memoirs, I describe how my mother arrived in Singapore having had a close escape from Pakistan, with a lot of antipathy towards Muslims.

“And she ended up falling in love with our Malay-Muslim neighbours. So that’s the story of Singapore, and that doesn’t happen in many countries in the world.

“Singapore is unusual; in parts of the West now, there is less tolerance of diversity. Singapore has always been tolerant of diversity, but also very disciplined – that each community must treat the other community with respect.”

Though Mr Mahbubani is retired from active roles, he remains busier than ever giving speeches around the world. He has already visited the United States four times this year, and plans on heading back there twice more before December. It helps, of course, that his 36-year-old daughter resides in New York, a city Mr Mahbubani regards as his “second home” having lived there for a decade.

He also has one son living in Pittsburgh and another in London.

Having travelled to more countries than he can remember, including parts of Africa and even Antarctica (he was on a cruise, and curiously insists it wasn’t that cold), he tells me he has yet to visit the Grand Canyon in Arizona.

“I have to get there before I get too old,” he says with a smile.

Before I leave his office, I gaze at a shelf where a framed photograph sits of Mr Mahbubani being received by former US president Ronald Reagan at the United Nations. On the wall behind his desk is another photo of him with former Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan.

“Who surprised you the most, in all your travels?” I ask.

“That’s a tough one, but I would say Narendra Modi,” he replies after some thought.

“I met him when I was chairman of the nominating committee of the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize, and Ahmedabad was shortlisted, so we went there to meet him.

“He was by far the most disciplined person I’ve met. He sat down with us and spent two hours just talking non-stop, describing very clearly what Ahmedabad was doing, what his vision for the city was and what his dream was.

“And, you know, we had gone to so many cities, met so many mayors, governors and chief ministers, and he was by far the most hardworking and most disciplined person.”

One wonders what music Prime Minister Modi listens to as he runs the country.

Photo: BANK OF SINGAPORE

Photo: BANK OF SINGAPORE