I was delighted to be featured on Lunch with Sumiko, which is one of the best-read columns in Singapore. When Sumiko invited me to lunch, I chose a coffee shop next to my childhood home, where my father would get caught in drunken fights. Sumiko’s story brings out some of my colourful childhood stories and provides a good preview of my memoirs, Living the Asian Century, which has just been released. I hope her column will also encourage you to read my memoirs.

Lunch with Sumiko

‘I’ve been misunderstood many times,’ says former diplomat Kishore Mahbubani as he releases memoir

Former Singapore diplomat Kishore Mahbubani tells executive editor Sumiko Tan that he’s lived by his mother’s advice to “put butter on your lips and smile” whenever he encountered setbacks in his career

Sumiko Tan

Executive Editor

Updated Jul 28, 2024, 05:46 AM

When Mr Kishore Mahbubani was at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a boss described him as a “deeply insecure person” in his annual appraisal.

He resented the criticism, but upon reflection felt there was some truth to it. Given how he had grown up in poverty, feeling insecure was probably a normal reaction.

Mr Mahbubani later came to find out that other higher-ups at the ministry had written “pages and pages of negative comments” about him over the years.

Unlike that boss, though, they didn’t share these assessments with him, even though there was a civil service rule that negative feedback had to be relayed to the civil servant.

“He was the only one who was honest enough to tell me, so in that sense he was a gentleman,” he says.

I’m having lunch with the 75-year-old former diplomat at Tiong Bahru Bakery in Crane Road in the Joo Chiat area.

We’re meeting to talk about his autobiography, Living The Asian Century: An Undiplomatic Memoir. The anecdote about the boss appears in the book.

Mr Mahbubani says he had “obviously upset a lot of people” during his time in the ministry, from 1971 to 2004.

“I must have come across as being very cocky and self-confident, and when you are cocky and self-confident, you invite detractors,” he says.

Are they still detractors, I ask.

“Less now,” he replies. “Now I have become irrelevant anyway.”

He’s being modest.

As he tells it himself, in the memoir and during the interview, his books on geopolitics, and the articles he has written in international media, have made him a sought-after commentator on Asia’s rise.

“The last seven years have been among the most productive years of my life,” he says. “The amount of global recognition that I’ve received has grown significantly.”

The memoir is an account of his difficult childhood and the ups and downs of his diplomatic career. Driven by ambition and a constant worry about money as he was supporting his immediate and extended family, he often fretted about where his job was heading.

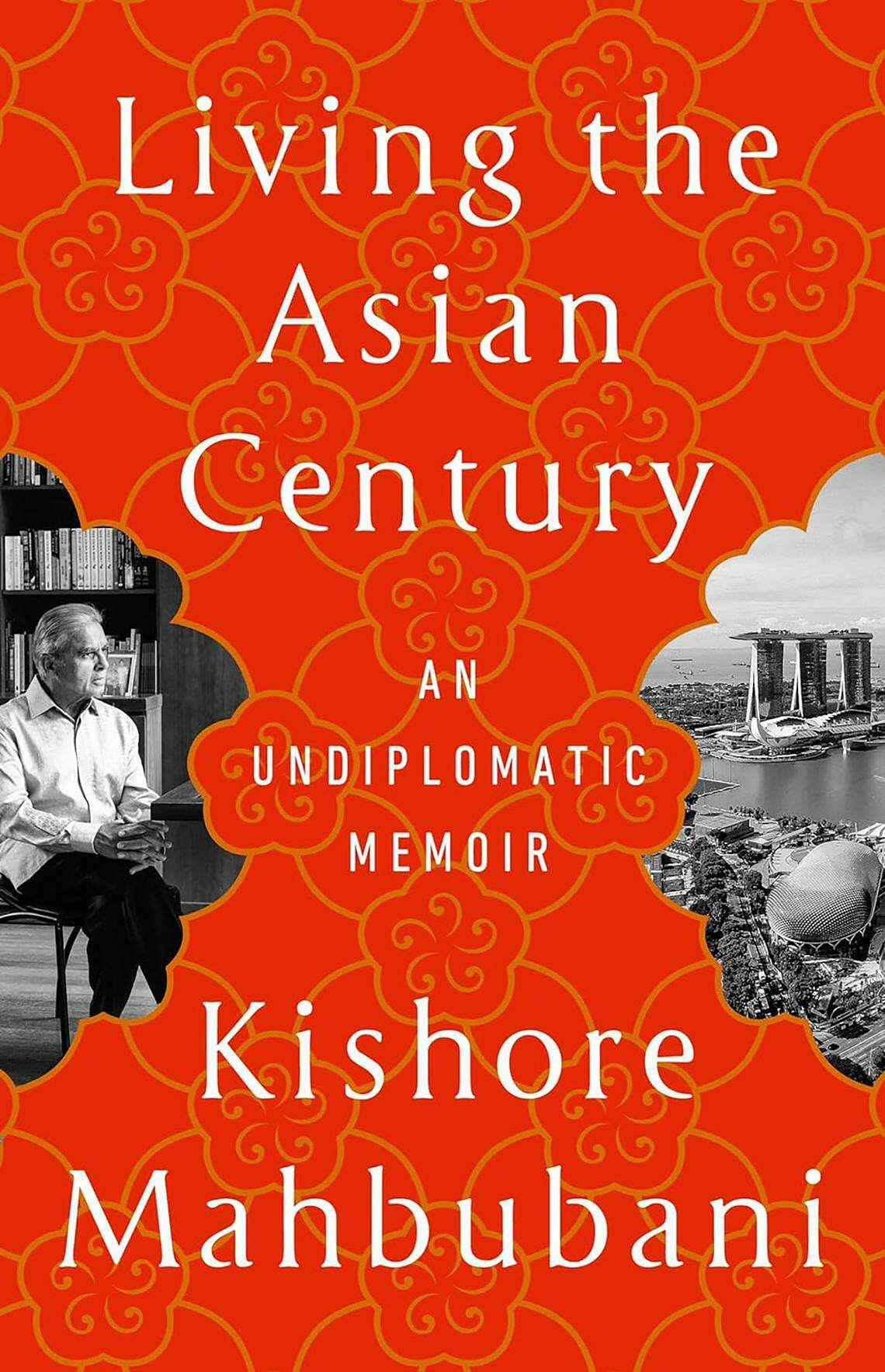

Mr Kishore Mahbubani’s autobiography, Living The Asian Century: An Undiplomatic Memoir, is an account of his difficult childhood and the ups and downs of his diplomatic career. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KISHORE MAHBUBANI

Mr Kishore Mahbubani’s autobiography, Living The Asian Century: An Undiplomatic Memoir, is an account of his difficult childhood and the ups and downs of his diplomatic career. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KISHORE MAHBUBANI

He recounts his interactions with Singapore’s founding leaders Lee Kuan Yew, Goh Keng Swee and S. Rajaratnam. He says he was invited by a minister to join the ruling People’s Action Party, only to meet “hostile” questions from Mr Lee during his interview. Among other things, he says, Mr Lee asked him: “Why don’t you have any friends?”

“I got rejected for a job that I was asked to apply for. That takes great skill, you know,” he tells me.

A large part of the book is devoted to his views on governance and international diplomacy. What will probably stay in readers’ minds, though, are anecdotes such as how he was “completely blindsided” when he found out his first wife had “found somebody else”, and his worry that their divorce would affect his promotion prospects.

“Most Singaporeans tend to be very discreet,” Mr Mahbubani says. “So in some ways, my memoirs are unusual in describing a lot of personal details.”

The memoir is his tenth book. Writing has turned out to be a lucrative career for him, with his previous books selling in the tens of thousands globally.

His first book, a collection of essays, was provocatively titled Can Asians Think? and released in 1998. Others in a similar vein followed, such as The New Asian Hemisphere: The Irresistible Shift Of Global Power To The East in 2008. In 2020, he released Has China Won?: The Chinese Challenge To American Primacy, cementing his reputation among detractors as an apologist for the East Asian giant.

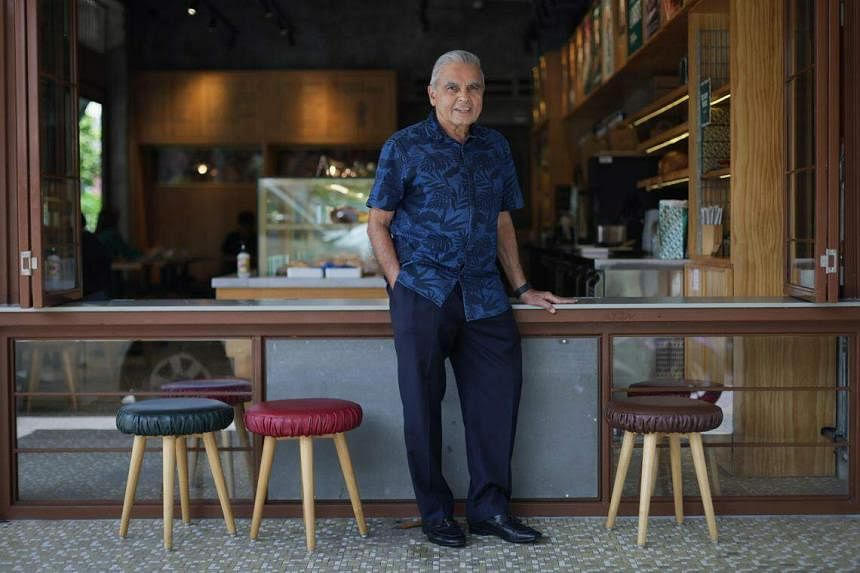

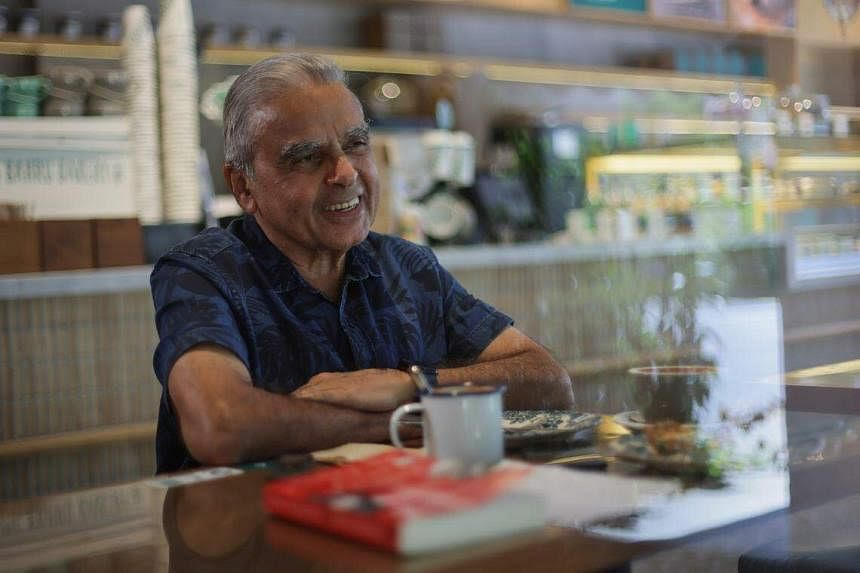

Writing has turned out to be a lucrative career for the 75-year-old former diplomat, who was with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 1971 to 2004. ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

Writing has turned out to be a lucrative career for the 75-year-old former diplomat, who was with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 1971 to 2004. ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

Covid-19 upended plans for a book tour in the United States, but interviews and speaking engagements he did over Zoom during the pandemic garnered thousands of downloads when uploaded on YouTube. The book has sold about 50,000 copies.

In 2022, he put out a free online book of essays titled The Asian 21st Century, which has had 3.58 million downloads in 160 countries.

He doesn’t get royalties from this e-book, but what he has made from his other books has been “significant”. He shares the figure for Has China Won? and let’s just say it’s enough to buy a decent mid-sized car.

Difficult childhood

In person, Mr Mahbubani is pleasant and has a calm manner.

He has chosen the location because across from Tiong Bahru Bakery is the small terrace house on Onan Road he lived in till he was in his 20s.

He is the second of four children and the only son in a Hindu Sindhi household.

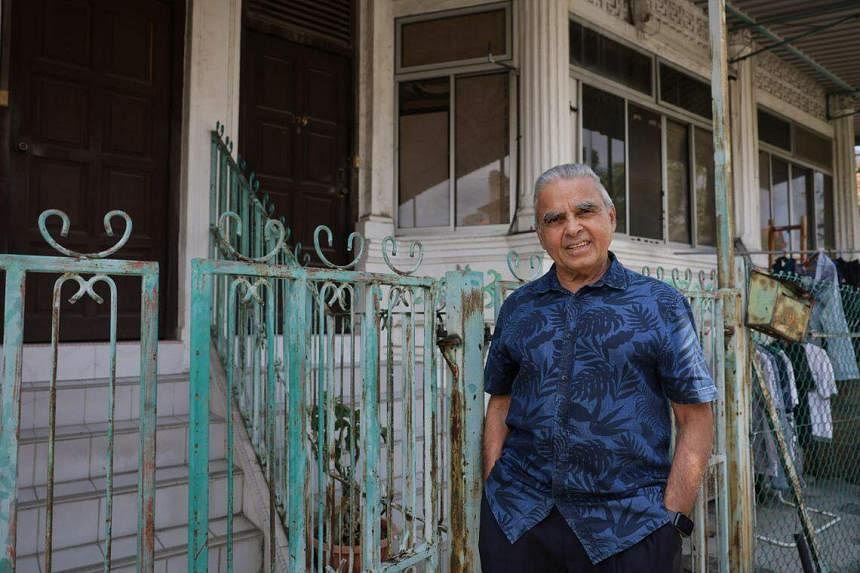

Mr Kishore Mahbubani lived at his childhood residence at 179 Onan Road (pictured in background) till he was in his 20s. ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

Mr Kishore Mahbubani lived at his childhood residence at 179 Onan Road (pictured in background) till he was in his 20s. ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

His father, Mohandas, couldn’t keep a job for long because of his drinking and gambling habits. At home, he had fits of drunken rage. When debt collectors knocked on the door, he would dive under the bed. “I’ll never forget the look of absolute fear in my father’s eyes,” Mr Mahbubani writes.

When he was 14, his father was jailed for nine months for criminal breach of trust after he gambled away some of his employer’s money.

“Even though my sisters and I resented (and sometimes hated) our father when we were young, I came to forgive him when I understood that life had dealt him a very bad hand,” he writes.

If his father was a self-destructive figure, his mother, Janki, was the family’s rock.

Her mantra to the children was: Even though poor, they must not reveal this or complain about it.

“In her words, ‘even if you are feeling hungry, don’t show it. Put butter on your lips and smile’,” he writes. “For a large part of my life, I walked around with deep insecurities while smiling with metaphorical butter on my lips to give the impression that all was well.”

Mr Kishore Mahbubani (left) with his parents and two of his sisters. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KISHORE MAHBUBANI

Mr Kishore Mahbubani (left) with his parents and two of his sisters. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KISHORE MAHBUBANI

The adversity of his childhood and his mother’s resilience made him a stronger person, he tells me.

A voracious reader, he was a good pupil at Seraya School and then Tanjong Katong Technical School, and loved his time at St Andrew’s School, where he attended pre-university. He was enchanted by the school’s pink building, enjoyed his subjects, made friends, and had teachers and a principal he admired.

He says the thought of going to university never crossed his mind. His elder sister had left school at 12 and his younger sisters dropped out at 16 and 18. After St Andrew’s, he started working as a textile salesman in a Sindhi store earning $150 a month, which he gave his mother.

“Then one of the greatest miracles of my life happened,” he recounts in the book.

He was offered a President’s Scholarship in 1967 to study at the then University of Singapore, which came with $250 a month. He still doesn’t know how he came to win the scholarship but puts it down to fate.

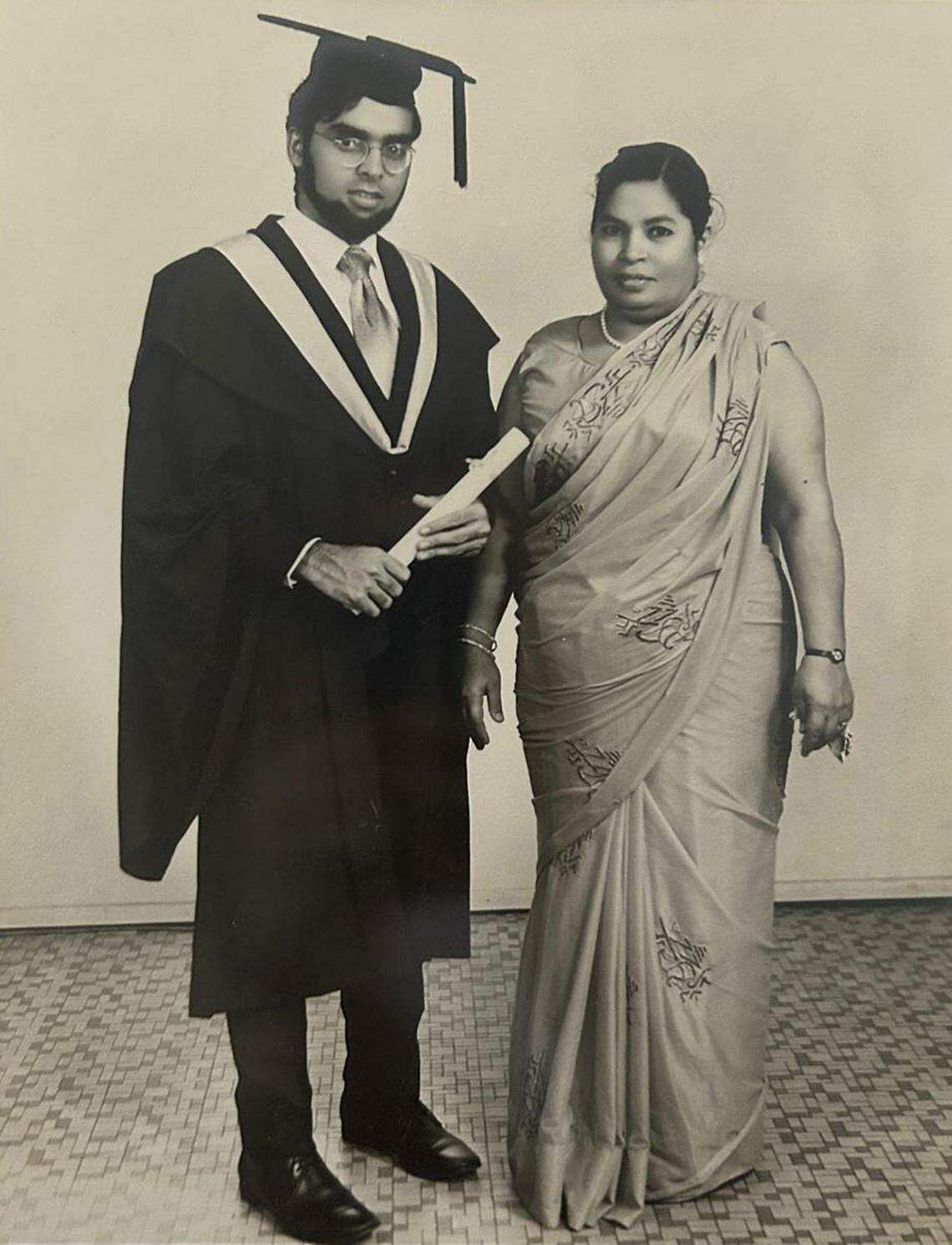

Mr Kishore Mahbubani and his mother after his graduation from the then University of Singapore. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KISHORE MAHBUBANI

Mr Kishore Mahbubani and his mother after his graduation from the then University of Singapore. PHOTO: COURTESY OF KISHORE MAHBUBANI

His chosen major, philosophy, which had excellent lecturers, developed in him a “free and independent spirit” to question “conventional wisdom on all counts”, he writes.

The scholarship came with a government bond, and he joined the Foreign Ministry in 1971, making $900 a month. Of that, he kept $100 and gave the rest to his mother.

He rose quickly. Two years later, when he was 24, he became charge d’affaires of the Singapore embassy in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. It was a dangerous posting with the Khmer Rouge shelling the city, but came with perks such as a bungalow with a housekeeper. It was a far cry from Onan Road.

There followed postings to the Singapore missions in Kuala Lumpur and Washington, where he met his second wife, Anne Markey, an American lawyer. She quit her job when they had their daughter and two sons.

In 1984, when he was just 35, Mr Mahbubani succeeded Professor Tommy Koh as Singapore’s permanent representative to the United Nations in New York.

Returning in 1989, he was appointed the founding director of the Civil Service College, then was promoted to permanent secretary at the Foreign Ministry.

A second posting to the UN in 1998 felt like “the single biggest demotion of my life” as he regarded it as a step down from being a permanent secretary.

But it was an exciting period. Singapore got elected as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council (UNSC) from 2001 to 2002, and also held the presidency of the council.

Chairing the council gave him a ringside seat to world affairs and the conduct of diplomacy. He concluded that power trumped principles, and saw at first hand the US domination of the UNSC.

“Many people, including many of my friends in Singapore, have little idea how brutal international relations can be, especially to small states. Small states are routinely reminded of the small space they have for manoeuvre, especially among the great powers,” he writes.

Back in Singapore, the realm of diplomacy exchanged places with academia when he became the founding dean of the National University of Singapore’s new Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in 2004.

The role gave him new skills, including fund raising. To new international students who wanted to learn about Singapore’s success, he introduced the acronym MPH: meritocracy, pragmatism and honesty. By the time he retired in 2017, the institute was known to be Asia’s leading public policy school.

His term, though, was also marked by how one of the school’s senior academics, Dr Huang Jing, was identified as “an agent of influence of a foreign country” by the Government and expelled in 2017. It’s an episode he does not want to comment on.

Pro-China?

A criticism of Mr Mahbubani’s writings is how he appears to be promoting China’s point of view and is “pro-China”.

He says this is the “biggest misunderstanding” of his work.

What he’s trying to do is “rebalance the global debate”, which is dominated by “strong and loud Anglo-Saxon voices telling us this is how the world is, this is how the world should be”.

“You never hear the Asian voices and so you get a very distorted perspective of how the world thinks.”

A criticism of Mr Kishore Mahbubani’s writings is how he appears to be promoting China’s point of view and is “pro-China”. He says this is the “biggest misunderstanding” of his work. ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

A criticism of Mr Kishore Mahbubani’s writings is how he appears to be promoting China’s point of view and is “pro-China”. He says this is the “biggest misunderstanding” of his work. ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

He posits that Asians, who form a very large part of the world’s population, tend to be culturally self-effacing and believe it is polite to choose to speak softly. Most Chinese are also not articulate in English.

“But I’ve learnt that unless you speak aggressively and boldly, your views don’t get heard. So I hope that by being incredibly strong and aggressive in my views, I am rectifying a global imbalance in the debate between East and West,” he says.

“But of course, to my Asian friends I come across as being very cocky, and self-confident and assertive, and they say, ‘Oh, this guy talks too much.’”

Paradoxically, the West appreciates his views “because they like debates and want to hear a different point of view”. He points out how he gets invited to speak at top American universities, and he likes to cite how former US treasury secretary Larry Summers named Has China Won? among his top three books of 2020.

He argues that giving the Chinese view is not at odds with Singapore’s stance on diplomacy.

It is not in Singapore’s interest to see the US become more aggressive in trying to bring down China. An acceleration of US-China friction would be disruptive for the world, and Singapore, being very trade-dependent, would be affected. “So what I’m doing is effectively defending Singapore’s national interests,” he maintains.

“The people whom I’m debating are the people who misunderstand China in the West. But of course in Singapore, since you don’t see the other side, you think ‘oh, Kishore is being very pro-China’.”

Straits Times executive editor Sumiko Tan with Mr Kishore Mahbubani at Tiong Bahru Bakery. ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

Some of his books have been translated into Chinese. As to the Chinese reaction to his views, he believes there’s “certainly appreciation that I’m trying to correct some misunderstandings of China but they don’t agree with everything I say”.

In 2017, a piece he wrote in The Straits Times about how “small states must always behave like small states” drew sharp criticism from senior diplomats Bilahari Kausikan and Ong Keng Yong, as well as Law and Home Affairs Minister K. Shanmugam.

“Questionable intellectually” and “muddled, mendacious and indeed dangerous” were some phrases used of the piece. Mr Shanmugam also said Mr Mahbubani’s assertion was contrary to some basic principles of Mr Lee’s which made Singapore successful.

What did he feel about the criticism? He shrugs and smiles.

“I’ve been misunderstood many times and, as you know, the flak didn’t damage me.”

He adds that it’s good to have different views in Singapore rather than to hold one standard line all the time. “If my article helped to contribute to debate, it’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

Though he is retired from active roles, he expects to be busier than ever giving speeches, given his belief that the most turbulent years in the US-China relationship are ahead.

He’s not done with books, either. He usually writes on weekends and does so by hand – “I’m not the generation that types”. He sends images of the pages to his research assistants at the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore, where he is an honorary Distinguished Fellow, to type up.

He is as much a prolific writer as he used to gobble up books. It takes him an hour to churn out 1,000 words and he writes while listening to Hindi songs by Indian singer Mohammed Rafi.

The next few months will be tied up launching his memoir in Singapore, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, New York and Harvard University.

In fact, “right now, my main problem is that there are too many opportunities thrown my way”, he says, citing speaking invitations from places as far-flung as South Africa, Finland and Abu Dhabi. After our interview, he is headed to Jakarta to speak on geopolitics at the invitation of Indonesian President-elect Prabowo Subianto, he says.

For someone who used to feel insecure about his place in the world, Mr Mahbubani seems finally at peace and able to lean back and appreciate, as he says in his book, “an exceptionally rich and rewarding life”.

- Living The Asian Century: An Undiplomatic Memoir is priced at $35.50 before GST.

What we ate

Tiong Bahru Bakery

7 Crane Road

1 tomato and basil quiche: $11.50

1 salmon and spinach quiche: $12.50

1 teh tarik: $7

1 latte: $8

Total (with tax): $46.76