by Kris Kong | Apr 30, 2020 | Interviews

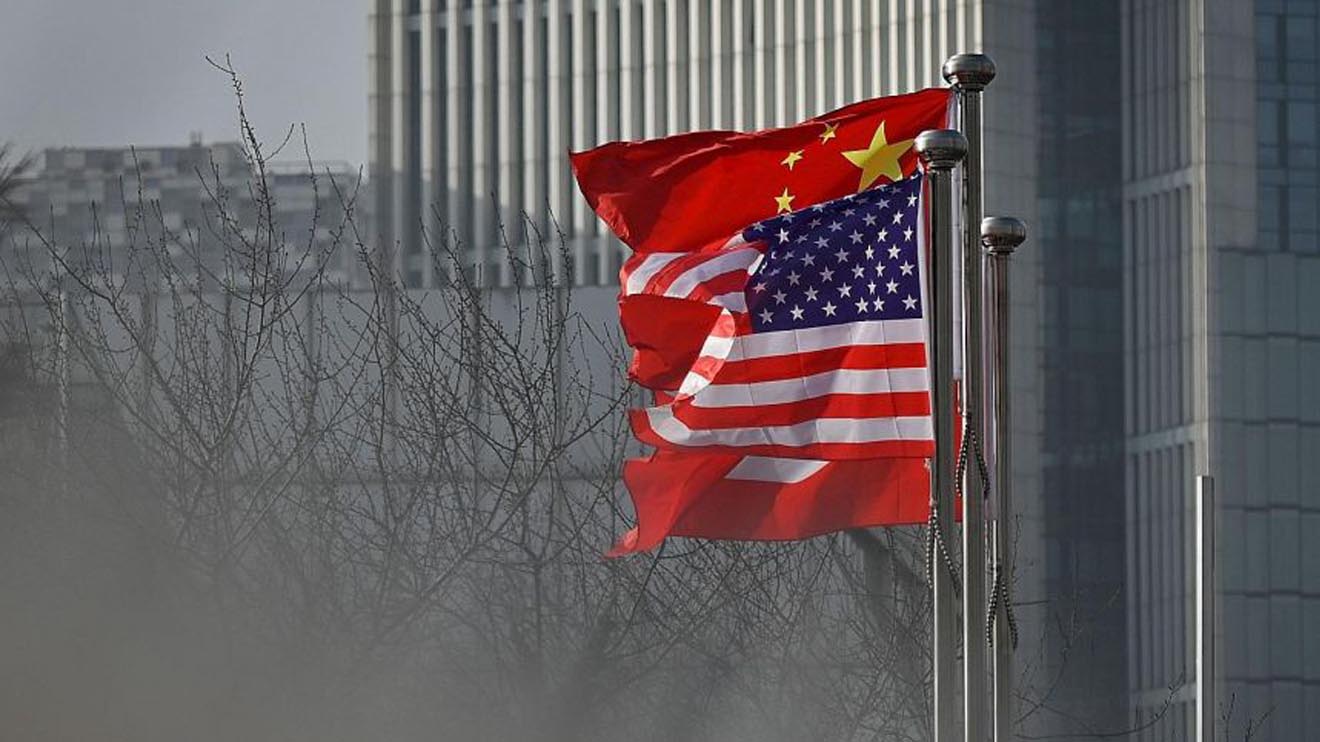

The massive global health crisis caused by the novel coronavirus over the past few months has enhanced the geopolitical contest between the US and China, said the distinguished Singaporean diplomat and academic. The world economy came to a screeching halt in 2020...

by Kris Kong | Apr 26, 2020 | By Kishore Mahbubani

One thing is certain. The geopolitical contest that has broken out between America and China will continue for the next decade or two. Although President Donald Trump launched the first round in 2018, it will outlast his administration. The president has divided...

by Kris Kong | Apr 22, 2020 | By Kishore Mahbubani

Kishore Mahbubani on the dawn of the Asian century The West’s incompetent response to the pandemic will hasten the power-shift to the east HISTORY HAS turned a corner. The era of Western domination is ending. The resurgence of Asia in world affairs and the global...

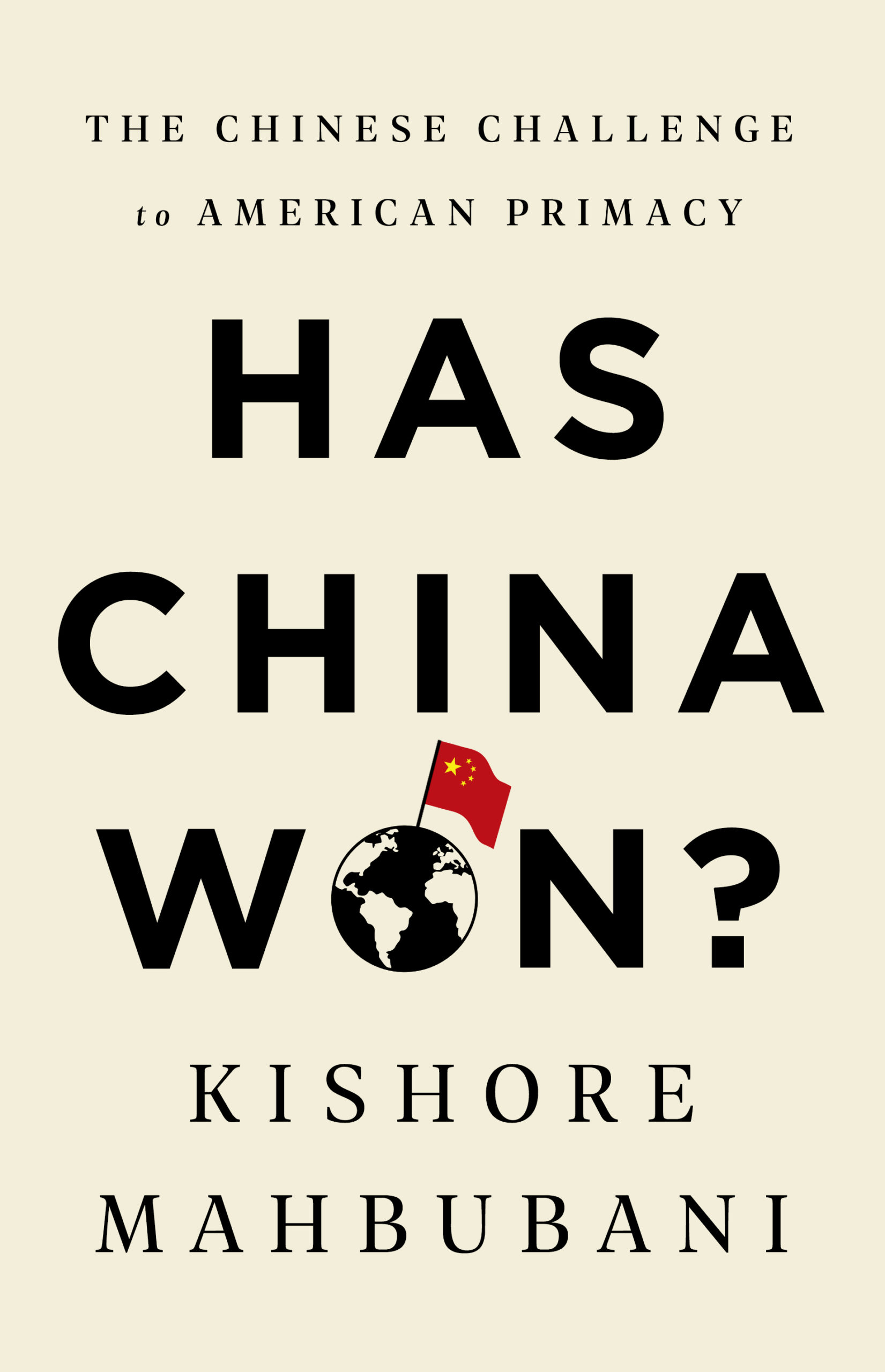

by Kris Kong | Apr 17, 2020 | Books

China and America are world powers without serious rivals. They eye each other warily across the Pacific; they communicate poorly; there seems little natural empathy. A massive geopolitical contest has begun. America prizes freedom; China values freedom from chaos....

by Kris Kong | Apr 16, 2020 | Interviews

While Donald Trump plays the Chinese threat card to re-mobilize his electorate, Beijing is stepping up propaganda operations to make people forget the origin of the virus and heal its image in the world Nothing is going well between the United States and China. In...